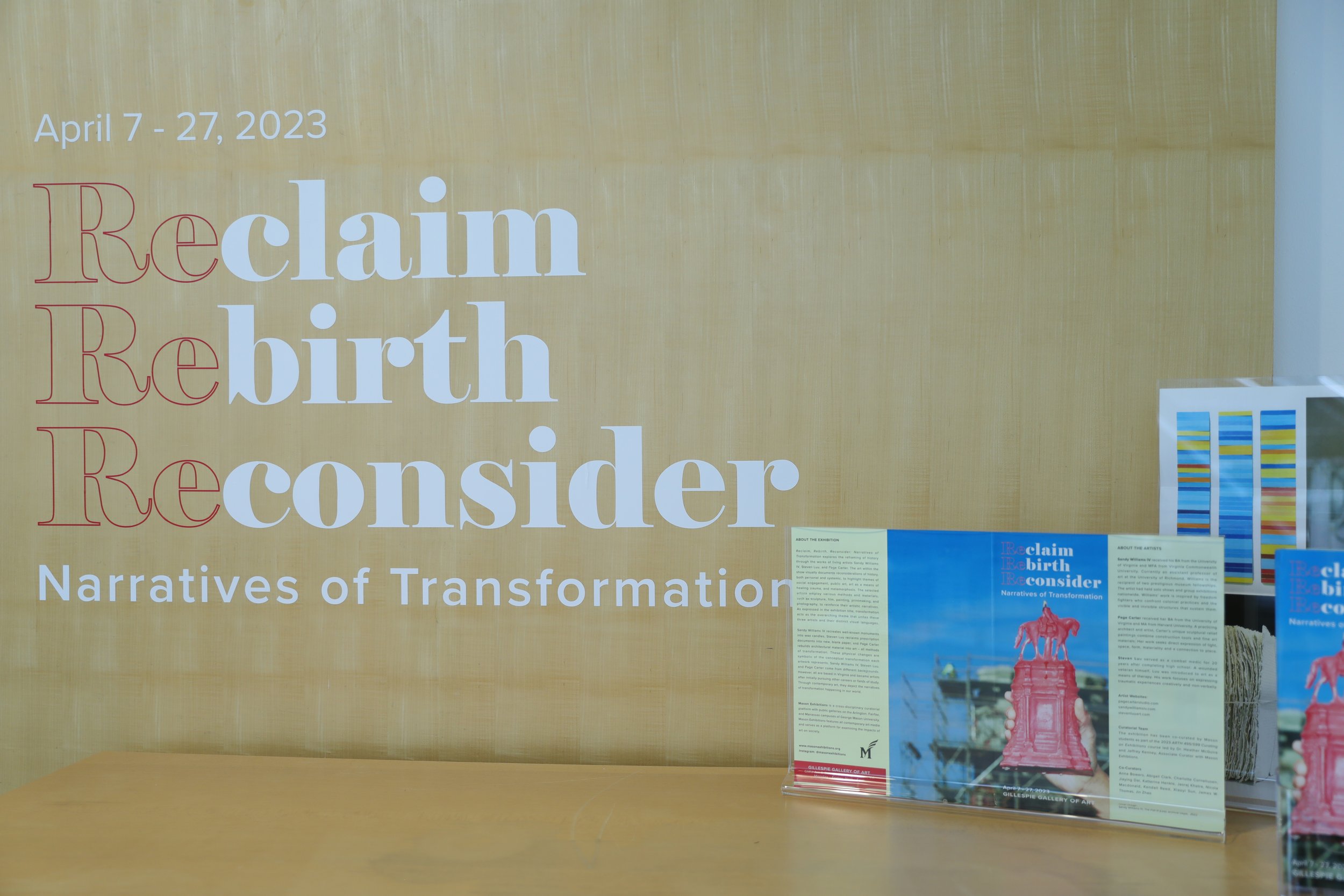

RECLAIM REBIRTH RECONSIDER

/RECLAIM, REBIRTH, RECONSIDER: NARRATIVES OF TRANSFORMATION

April 7 - April 27, 2023 @ Gillespie Gallery

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Reclaim, Rebirth, Reconsider: Narratives of Transformation explores the reframing of history through the works of living artists Sandy Williams IV, Steven Luu, and Page Carter. The art within the show visually documents reconsiderations of history, both personal and systemic, to highlight themes of social engagement, public art, art as a means of healing trauma, and metamorphosis. The selected artists employ various methods and materials, such as sculpture, film, painting, printmaking, and photography, to reinforce their artistic narratives.

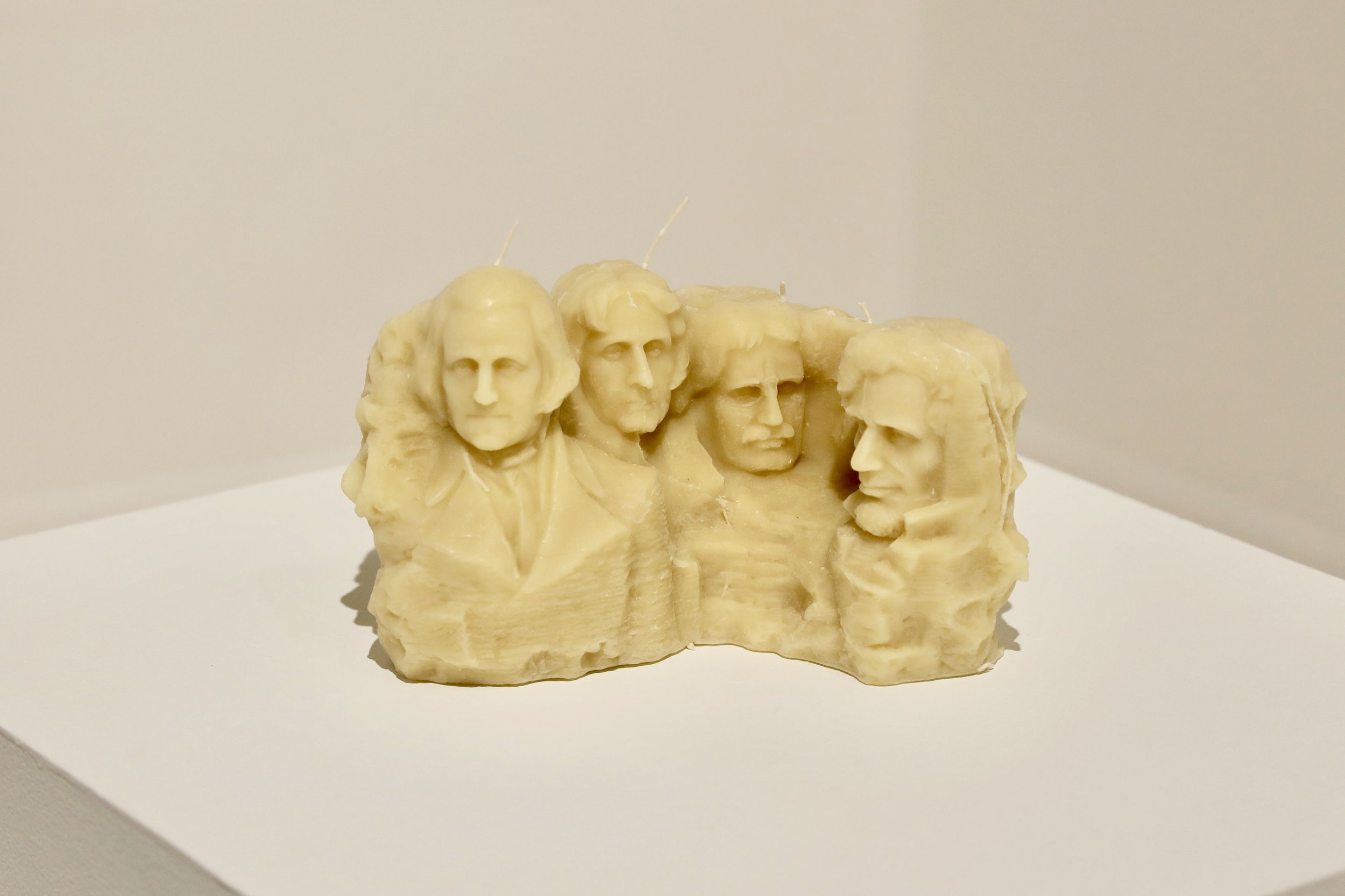

As expressed in the exhibition title, transformation acts as the overarching theme that unites these three artists and their distinct visual languages. Sandy Williams IV recreates well-known monuments into wax candles, Steven Luu reclaims prescription documents into new, blank paper, and Page Carter rebuilds architectural material into art – all methods of transformation. These physical changes are symbolic of the conceptual transformation each artwork represents.

Sandy Williams IV, Steven Luu, and Page Carter come from different personal backgrounds. However, all are based in Virginia and became artists after initially pursuing other careers or fields of study. Through contemporary art, they depict the narratives of transformation happening in our world.

The exhibition is co-curated by Mason students as part of the Art History “Curating an Exhibition Course,” with Dr. Heather McGuire.

ABOUT THE ARTISTS

Sandy Williams IV is an interdisciplinary artist and educator, currently working as an Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Richmond. They earned a BA in Studio Art from the University of Virginia and an MFA in Sculpture and Extended Media from Virginia Commonwealth University. Their work investigates time, emancipation, and collective memory through research-based, participatory, and site-specific art projects. As seen in Williams’ sculptures, film, and photography featured in this exhibition, they invite audiences to reconsider the dominant narratives of history exemplified by monuments and reclaim public spaces. Williams is a recipient of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Artist Fellowship and the New York Community Trust Van Lier Fellowship. Their art has been featured in museums and galleries across the United States and internationally. Williams received solo exhibitions at 1708 Gallery in Richmond, the Visual Arts Centre of Clarington in Ontario, Reynolds Gallery in Richmond, and Second Street Gallery in Charlottesville.

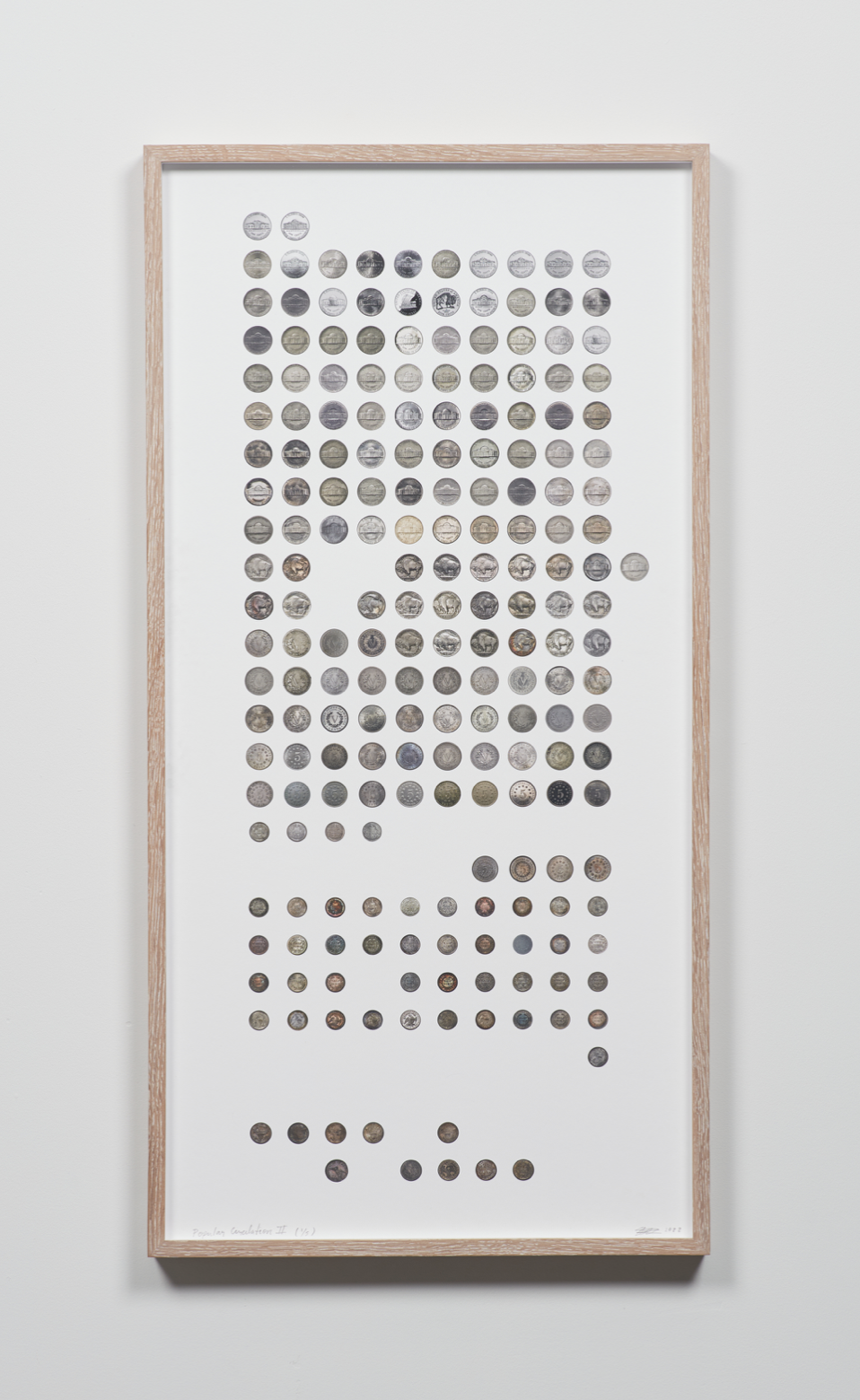

Interview with Steven Luu

Steven Luu escaped Vietnam during the Communist depression when he was seven and served as a U.S. Air Force combat medic for two decades after high school. Because of these experiences, death and healing are prominent themes in his sculptures. Wounded in combat, physically and psychologically, Luu was introduced to art as a means of therapy through an intensive treatment program at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. He explored art as a vehicle for communicating deeply rooted trauma in a non-verbal manner. Developing his connection to art in a formal sense, Luu attended George Mason University and earned a BA in Theology and a BFA with a concentration in sculpture. He now works alongside multiple art therapy programs working with trauma recovery. His artistic practice relies heavily on repetition, industrial materials, and order to reinforce art to transform trauma into a form of self-healing. Luu’s sculptures in this exhibition reconstitute his medical paperwork relating to the fourteen daily medications he relies on to maintain his mental health. By exploring material and process, Luu has reinvented his own narrative through art.

Page Stephenson Carter is a trained architect and practicing artist that lives and works in Millwood, Virginia. She received her BA in Art History and Studio Art from the University of Virginia and an MA in Architecture from Harvard University. In addition, Carter founded and led a small architectural practice that specialized in modern design. Carter uses her architectural background to inspire her artwork, often using architectural and construction tools in combination with fine art materials. Her work includes traditional canvas paintings and sculptural relief paintings where she aims for ambiguous art that is neither wholly abstract nor entirely representational. Instead, using color and texture, Carter achieves undulating, topographic surfaces that connect to specific emotions, places, and times. Carter’s art has been included in several group exhibitions in Virginia and one in Oregon at the Pacific Northwest College of Art. Page Carter’s relief paintings in this exhibition transform architectural materials into art to explore historical narratives.

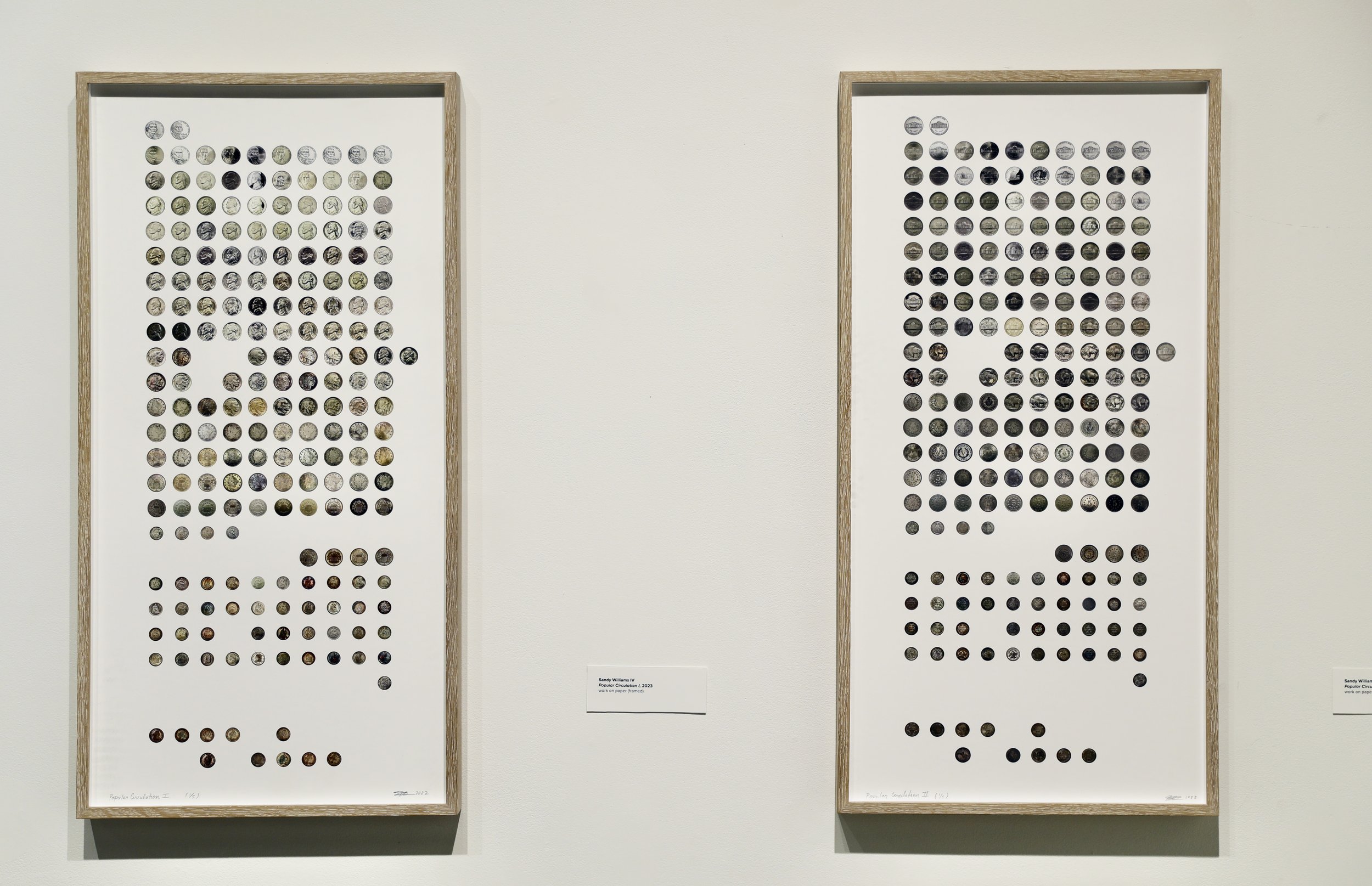

INSTALLATION IMAGES

CURATORIAL STATEMENT

Art as Healing and Connection

Through The 40 Acres Archive, Williams recalls the government’s unfulfilled promises and institutional failings during the Reconstruction Era, leading to the systemic inequalities Black Americans face today. For example, following the Civil War, approximately four million newly freed people were supposed to receive up to 40 acres of redistributed land, including the site currently known as Chimborazo Park. From 1865 to 1866, a community of 2500 Freedmen built homes and classrooms on the grounds of the abandoned Chimborazo Hospital. For these newly emancipated people, their community represented opportunity and peace. Unfortunately, this community only lasted a year before the federal government evicted its residents. To honor this forgotten history, Williams worked with a skywriting crew to trace the dimensions of a 40-acre plot in contrails.

The skywriting performance opened the conversation about reparations to an amplified visual field. This project provided possibilities for community interaction, including witnessing skywriting, meeting new people, and realizing that the area is much more than a recreation site. By connecting with social practice art, viewers’ identities exceed passive recipients. They become active participants contributing recorded actions and valued opinions. Finally, by acknowledging the original residents of Chimborazo Park, the land will hopefully become a place of healing.

We ask, “What is the purpose of art in one’s life?” hoping that viewers will have the opportunity to express themselves, connect with each other, strengthen communities, and perhaps begin a journey of endless possibilities.

-Charlotte Corneliusen, Gloria Dai , Jin Zhao, James W. Thomas

What is the purpose of art in our lives? For centuries, people have used art to heal. Art cannot substitute medication or surgery. It can, however, bring us inspiration, wonder, joy, and what we need most in everyday life – hope. In the presence of art, we engage not just our eyes but our hearts; we connect to the artist and others who have stood before us in front of the same artwork. Creating a connection between artists and viewers, between us and others, is perhaps one of the most crucial roles of art and healing.

In this exhibition, two featured artists, Steven Luu and Sandy Williams IV, decided to become artists after participating in art therapy programs while undergoing treatment for serious medical conditions. Their art encourages public participation and collaboration. Luu and Williams’ unique artistic expressions help reinvent personal and collective identities and memories.

Steven Luu creates sculptural installations that deal with traumatic experiences resulting from early childhood adversity and numerous deployments to the Middle East. Diagnosed with PTSD, Luu experienced prolonged grief and guilt after returning from Afghanistan. He tried medication and counseling, receiving up to 11 medicines monthly, and eventually found his way to healing through art. Luu uses materials such as pill bottles and prescription labels to reinvent his narratives. Through the process of shredding, blending, and repurposing prescription insert papers, he makes art as a model for translating a tragic past into a reborn life.

Sandy Williams IV creates small wax casts of monuments that symbolize racial oppression and violence. The artist burned the wax sculptures in front of the bronze monuments while they stood. Although Richmond’s Confederate monuments have been removed from their pedestals, the miniature wax versions are available for purchase. In addition to providing symbolic healing, sales of Williams’ wax monuments in July 2020 raised $6,672 for the Jackson Ward Youth Peace Team, a community organization for underprivileged black teenagers.

Monuments

However, as Monument Lab has taught us, even a statue is constantly changing. Stone cracks and crumbles if not maintained. Iron corrodes and rusts, and even corrosion resistant bronze develops a patina. The monuments themselves are constantly changing, even with maintenance, much like our perception of them. Robert E. Lee may have been celebrated as a hero by some, but time has allowed us to acknowledge his connections to slavery, segregation, and the confederacy. Like his monuments, the larger conversation around him has changed.

Artists featured in this exhibit and non-profit groups such as Monument Lab are creating resources and works to encourage nuanced conversations around the effect that monuments have on the public at large. Whether it’s showing us how monuments have been taken down, or how objects from the past can be reworked and transformed, the art reflects that. The artists engage with these monuments and the meanings they hold in the past, the present, and the future.

-Abby Clark and Joy Khatra

Civil war monuments have long been a part of the Southern United States’ public visual history. Abraham Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson are among the top fifteen most monumentalized individuals in the United States according to Monument Lab, a non-profit public art and history studio with whom we consulted in preparation of this exhibition. Each of these individuals can be seen in the works present here.

Studies and discussions surrounding these monuments began long before the nationwide protests following the death of George Floyd brought monuments from around the south, especially those in Richmond, VA, to the forefront of American minds. As these discussions continue, many monuments around the country have been removed. In the case of Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Confederacy, the city removed all city-owned Civil War monuments. They were placed in a graveyard of sorts, in a location kept secret for security, and ownership was handed over to the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia.

The Confederate monuments that were taken down in Richmond, and throughout the country, have always been thought of as permanent, resilient to change.

Reconsidering History

Luu takes agency over the difficult parts of his own personal history in the transformation of the prescription papers, creating both art and a healing process. Luu’s paper stacks and their corresponding video suggest that the rewriting takes place in the artistic process, not the result.

Page Carter reconsiders history by presenting the urgency of recent history through the visual representation of statistical data of the increase of the Earth’s average temperatures. Through her vibrant use of color and unbalanced composition, Carter effectively depicts the data in a comprehensive, artistic way. In addition, Carter uses materials frequently used in architectural projects, such as roof shingles and house paint. In her other works, Carter uses paint swatches to facilitate a “connection to place,” creating an interesting non-linear temporal connection between her work and local history.

The past is widely considered completely fixed and unchanging; however, art has an intrinsic ability to reach and form connections among people, and because of this it is an ideal format for reconsidering history.

-Anna Bowers, Katt Henkle, and Nicola Macdonald

Reconsidering history takes many forms, but generally involves questioning a history, whether it be personal, national, or global, as it has traditionally been represented. Through the works of Sandy Williams IV, Steven Luu, and Page Carter, we are taken on a transformative journey of reconsidering different histories.

Sandy Williams’ monument candles rewrite history by transforming stable monuments into impermanent monuments, suggesting that both history and monuments should change. Traditional monuments are static and changeless, symbolic of the unchanging nature of the usual representation of history. In contrast, Williams’ wax candles are impermanent and transformative, allowing for the reconsideration of monuments and their connection to history. William’s candles offer a contemplative space to imagine how these reconsiderations may take shape in the future.

Luu also embodies the idea of reimagining history. Luu challenges the permanence of perhaps his most vulnerable self and reframes it as a steppingstone towards his later transformation. By using old prescription papers that are reinvented to form fresh blank paper, Luu establishes an understanding that our histories are not fixed but instead can be healed and transformed into a new form.

The Trauma of War and Violence

Williams’ The (Bronze) Wax Monuments and The Fall I - IV series highlight figures and forces from this era that have been suspended in time through the use of monuments that promote antiquated wartime ideologies of racism and violence.

Steven Luu approaches traumas of war and violence through a means of personal healing of the psyche and a reflection on his physical healing. Luu works with fellow survivors of trauma to create art as a means of therapy to combat the damage done to his psyche through traumatic experiences. Former works from Luu have been made with materials from his role as a combat medic. Reinventing My Narrative, showcased in this exhibition, has been made with recycled medications and medical paperwork that Luu relies on as a result of physical and mental trauma.

Page Carter’s art documents the systemic impacts of trauma on the environment as war and violence act as significant contributors toward the climate emergency. The climate crisis drives many countries closer to domestic violence, heightening the chances of global civil wars due to political instability, poverty rates, and increasing food insecurity. This is prevalent in Carters Warming Stripes USA 1910 - 2017 as the first yellow and orange shims on the work correspond with the years of the first World War and are representational of how environmental trauma and exploitation have impacted our climate.

-Kendall Reed

The artists’ work showcased in Reclaim, Rebirth, Reconsider: Narratives of Transformation respond to the impacts of trauma relating to war and violence. Trauma can be understood in two ways, the first being a distressing emotional experience or an injury to the psyche and the second being a physical injury to someone or something. Williams’s art acts as a response, reaction, and curated memory of war and violence on the collective psychology of Black Americans. His work addresses the first definition of trauma surrounding the systemic relation between race and violence, specifically slavery and the monumentality of civil war trauma within the South, focusing primarily on Virginia.

Steven Luu’s narrative acts as a bridge between both definitions of trauma as he directly responds to emotional and physical first-hand experiences with war, weaponry, and politically affiliated violence as a child in Vietnam and as a combat medic throughout early adulthood. He creates art with the materials of his trauma, working with the medications he uses to thrive post-war as a medium and method. Page Carter’s work has a more detached and physical relation to war and violence, aligning her artistic narrative with the second definition of trauma. Her works deal with physical impacts on the climate, to which the U.S. Department of Defense has contributed roughly 80% of all federal government energy consumption since 2001. Carter’s work documents the progression of climate trauma, temperature precisely, which has closer connections to war than commonly understood.

The legacy of slavery and the ‘heroic’ imagery used in contemporary racist narratives is heavily explored in Sandy Williams’ 40 ACRES series, which presents an order that President Andrew Johnson rescinded following the Union’s victory during the Civil War that granted land to freedmen.

EXHIBIT IMAGES

RECEPTION IMAGES

ABOUT MASON EXHIBITIONS

With galleries in Arlington, Fairfax, and Manassas, Mason Exhibitions offers a multi-venue forum for the presentation of contemporary visual artists who advance research, dialogue, and learning around global social issues.