Resistance to these ordinances sparked the beginning of the Haitian Revolution. On August 22, 1791, Boukman Dutty, accompanied by an elderly priestess, performed a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caiman, during which they used the "war-like petro spirit of Vodou to organize, plan, and give the signal that began the revolt." During the Revolution, Catholicism almost disappeared as French priests fled the country in protest and in fear for their lives. After the end of the Revolution, the Vatican refused to acknowledge Haiti as a republic, causing a further rift between the Catholic Church and Haiti. In an attempt to regain favor with the Vatican, King Henri Christophe declared Catholicism the official religion of Haiti and sought to suppress Vodou. During this period, Haitians practiced Catholicism in public while keeping Vodou ceremonies private.

Between 1807 and 1842, Haitian presidents worked with the Catholic Church to eradicate Vodou by stamping out the cultural significance of Vodou or trivializing it as folklore. However, with the election of President Faustin Soulouque in 1847, Vodou became more publicly acceptable. Soulouque encouraged the practice of the religion, and members of Hait's elite were able to openly embrace Vodou as a part of their culture. "Catholic orthodoxy rapidly declined as several generations of Haitians received no religious instruction in the faith.

With the appointment of President Fabre Nicolas Geffrard, the rift with the Vatican was healed through the 1860 Concordat. This agreement once again brought Vodou under scrutiny, sparking the anti-superstitious campaigns of 1896, 1913, and 1941, during which ritual paraphernalia was burned throughout the country. As a last-ditch effort to destroy Vodou influence in 1941, President Elie Lescot's government and the Catholic clergy waged what Murrell called "an all-out 'demon hunt' war against Vodou" in an attempt to "save the souls of Vodou devotees from eternal damnation."

Occasionally, Vodou was even weaponized against the Haitian people. François Duvalier presented himself as the embodiment of Vodou powers to instill fear in the peasant class. He encouraged this perception by positioning himself as a servitor or devotee of the Iwa and as a boker (priest who engages in sorcery), as well as by imitating the dress and personality of Baron Samedi, the Iwa of the dead." Despite the renunciation of Catholicism during the Duvalier dictatorships, the American occupation of Haiti and the post-Duvalier era saw further persecution of Vodou.

'The Haitian Constitution of 1987 finally established freedom of religion in Haiti. President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, elected in 1990, further supported this freedom and allowed Vodou devotees to practice without political and religious repercussions. In 2003, Aristide enacted legislation that allowed Vodou to be recognized as a legitimate and official religion. Because of this ruling, his image appears on many Vodou altars."

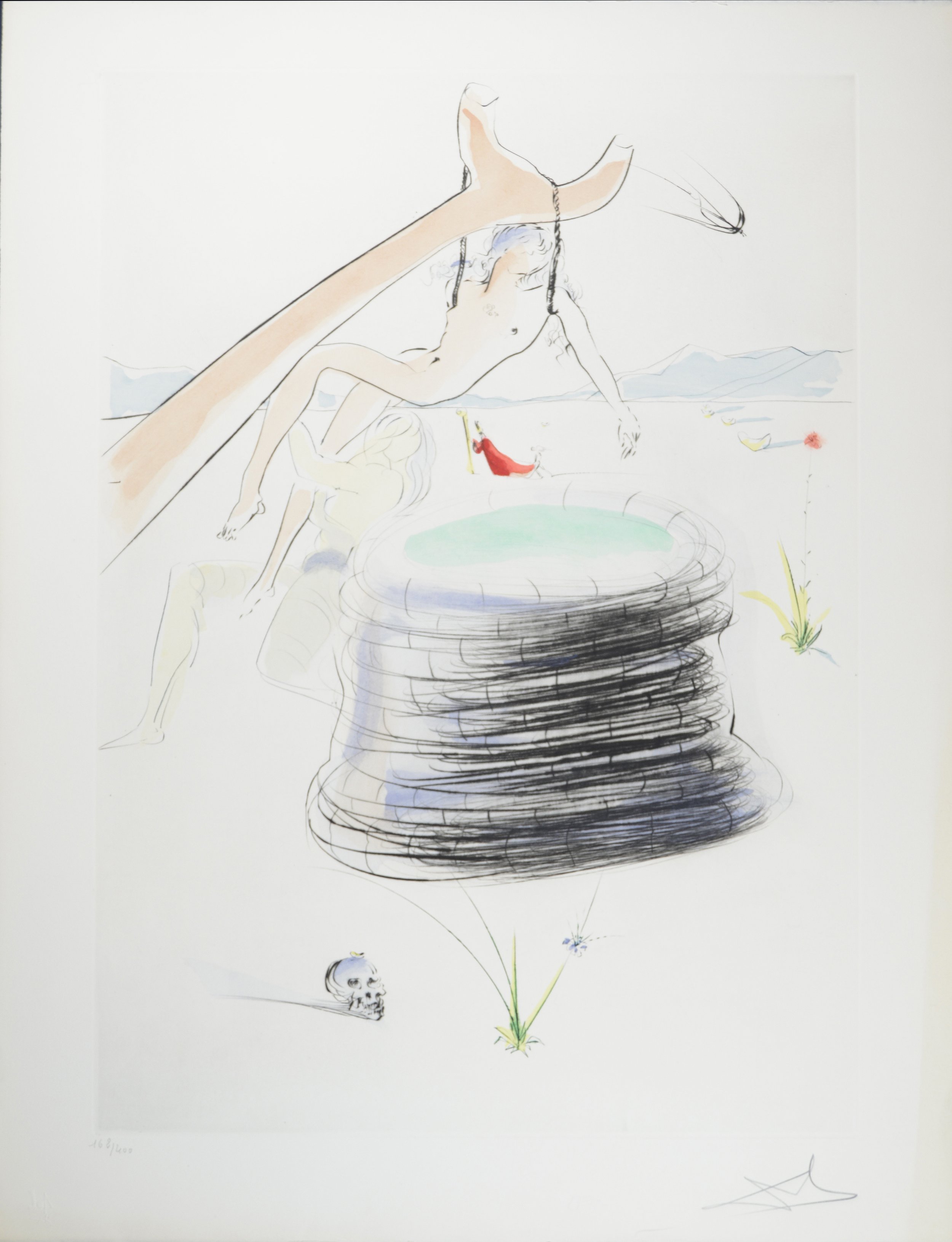

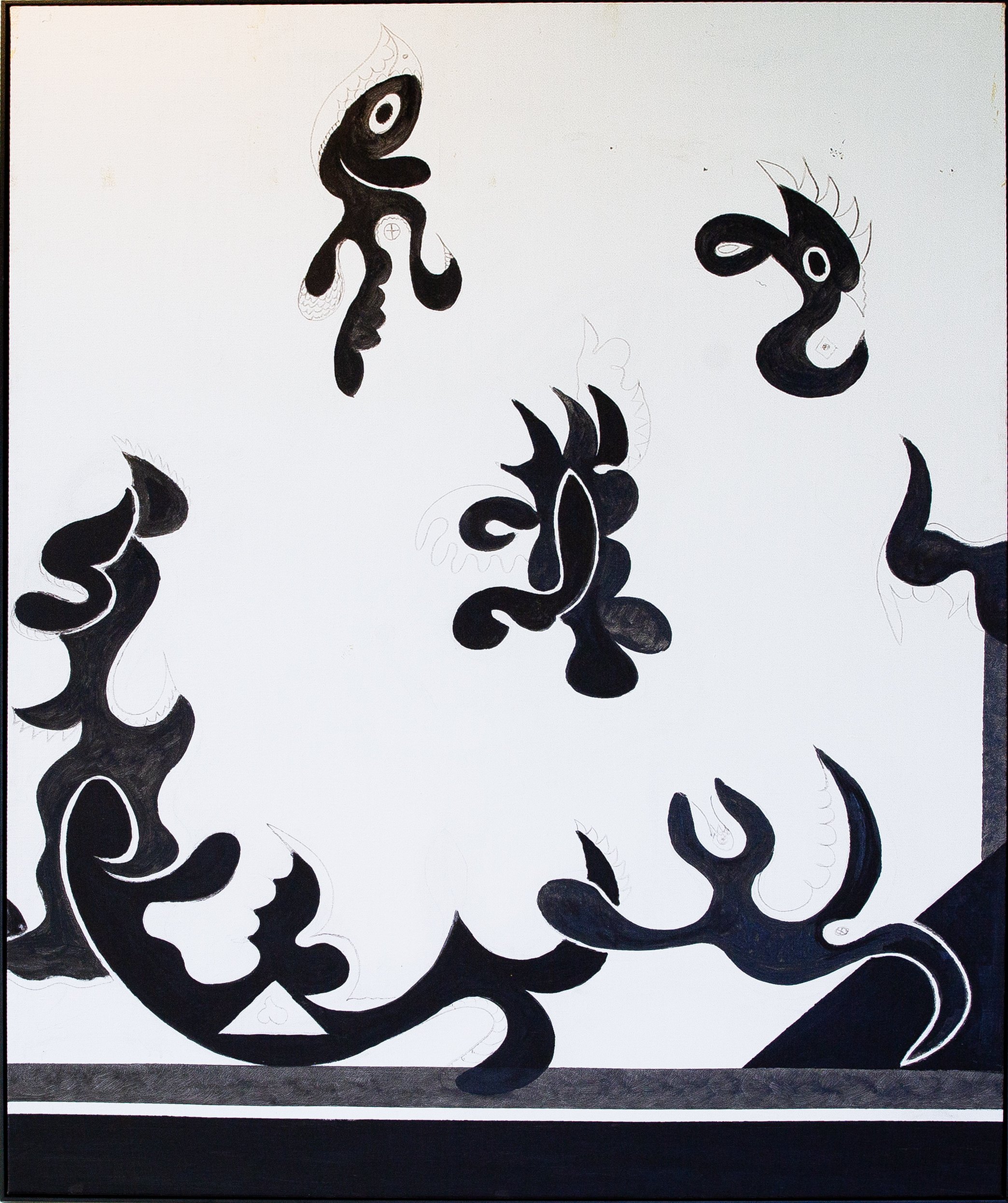

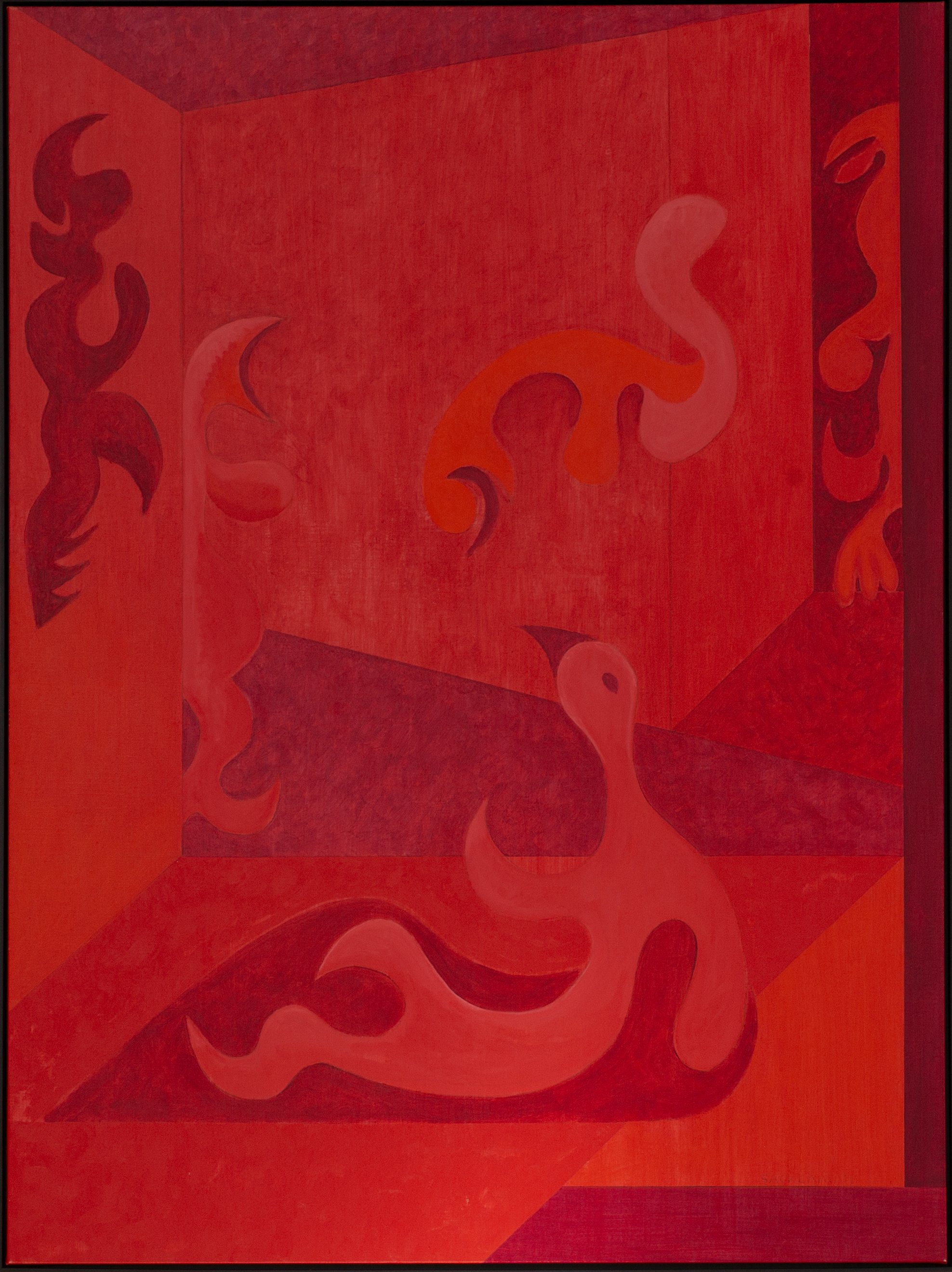

Paintings from the Kravitz collection highlight this historical and religious intermingle. Several works include biblical imagery, such as Obès Faustin's Jungle Scene with Animals (Garden of Eden?) and Gabriel Bien-Aimé's Adam and Eve. Saincilius Ismaël's Nativity Scene is an excellent example of religious syncretism. While the main subject is the Christian nativity scene, the heart symbols refer to Er-zuli, the Vodou Iwa (spirit) of love and motherhood. She could also be interpreted as Ezili Danto, another manifestation of Erzuli. Ezili Danto is often shown in red and blue, as the Virgin Mary is depicted in this painting. Ezili Danto is often equated with the Virgin Mary or other iterations of Madonnas with children.